What’s the password?

- May 12, 2020

- 3 min read

by Evangeline

How do you tell a Kiwi apart from an Aussie? The clue is in their favourite food. As Aussies tend to have broader vowels and Kiwis, lower vowels, in Australia, you would have feesh and cheeps, while in New Zealand, you would have fush and chups. Evidently, the difference lies in their pronunciation.

How do you tell an Aussie apart from a Singaporean (Singlish speaker)? Well, their pronunciation. In the most colloquial form of Singlish, their becomes diar, three becomes tree, with becomes wif ... and so on. A lot of these pronunciations are largely a legacy of the early English teachers in Singapore – such as the Catholic French and Irish nuns, and Indians and Sri Lankans from the British Indian subcontinent – all of whom had an inability to produce certain English phonemes which did not exist in their native tongues.

The pronunciation of words (or phrases) is fascinating and at the same time, a powerful linguistic device that can distinguish and identify people. Unless we learned two or more languages when we were young, very often, our tongues would have the muscle memory to produce only the specific sounds peculiar to its mother tongue. Give it an unfamiliar sound, and what comes out of our mouths would simply be the closest sound from our native language.

There are ample stories throughout history of the use of pronunciation as a practical tool. One such example is of passwords, used to identify friend or foe. In the Pacific theatre during the Second World War, American soldiers always used passwords such as ‘lollapalooza’ or ‘priest’, which contained the letter ‘L’ or consecutive consonants like ‘pr’ or ‘st’. This was because Japanese speakers tend to confuse ‘L’ and ‘R’, and are in the habit of ending every syllable with a vowel (with the exception of ‘N’). Hence, upon hearing the first syllables returned as ‘rorra’ or ‘puri’, the American soldiers would immediately open fire without seeing their faces or even waiting to hear the rest.

Similarly, over in Holland, the Dutch used words like ‘Scheveningen’ (a place in the Netherlands), while in Denmark, the Danes apparently used phrases like ‘Rødgrød med Fløde’ (red currant berry pudding with cream), all of which are almost impossible for non-native speakers of the respective languages to pronounce.

These passwords worked, simply because they were a means of identification that distinguished a particular group of people from another. Such passwords have come to be termed as ‘shibboleths’. Interestingly, the origin of this term goes back to Judges 12:5-6 in the Old Testament, in which a similar event to those told above took place:

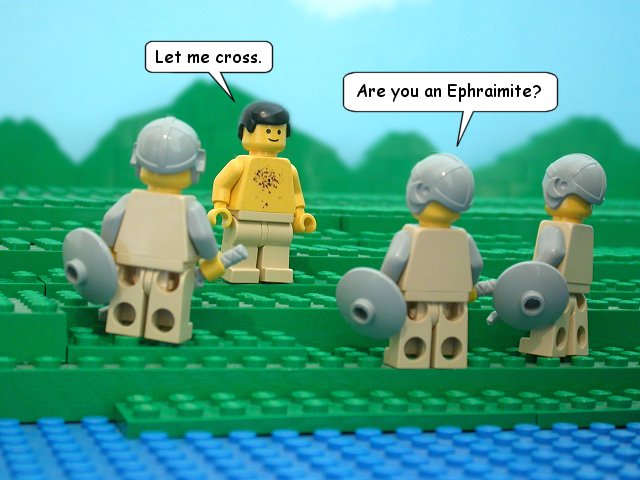

The Gileadites captured the fords of the Jordan leading to Ephraim, and whenever a survivor of Ephraim said, “Let me cross over,” the men of Gilead asked him, “Are you an Ephraimite?” If he replied, “No,” they said, “All right, say ‘Shibboleth.’” If he said, “Sibboleth,” because he could not pronounce the word correctly, they seized him and killed him at the fords of the Jordan. Forty-two thousand Ephraimites were killed at that time.

from The Brick Testament (click arrows in the images to view story)

Today, the definition of shibboleths has been extended to include more than just passwords, or specific words and phrases. During the conflict in Northern Ireland in the latter half of the 20th century, one could tell a Protestant apart from a Catholic just by how he or she referred to a particular city in Northern Ireland. Protestants, who were generally supporters of the United Kingdom, would call it Londonderry, while Catholics, who were for a united Ireland, would simply call it Derry.

In other accounts of WWII, the Allied powers also used the test of the Star Spangled Banner on suspected Axis spies posing as American soldiers. Asked to recite the song, which is also the American national anthem, spies would belt out the whole four stanzas perfectly, only to be caught immediately. Why? Because most Americans (then and now) would only be familiar with the first stanza, which is the part most commonly sung as the national anthem!

While all of the stories here suggest that shibboleths can be of both linguistic and non-linguistic elements, one thing we can conclude is that language can be a strongly-felt part of a person's identity, and can also distinguish one group from another (sometimes leading to division!). This is why at Wycliffe, we believe that helping people retain the use of their language protects their cultural heritage and identity. The only difference is that, in God’s kingdom, a multitude of languages causes no division and has neither friend nor foe. It is simply an expression of God’s wonderful creativity.

And the best part of God's kingdom? No password is needed to enter – just His grace.

Comments